OPENING: Saturday, 18th ot July 2020, 3 Pm, Schloss Karlsdorf bei Ilz

INTRODUCTION: Günther Holler-Schuster

The exhibition is also opened on 19.7. & 25. and 26.7.2020 from 3 – 6 Pm

Route from Graz / Route from Vienna

REGISTRATION REQUIRED

+43 699 123 814 22

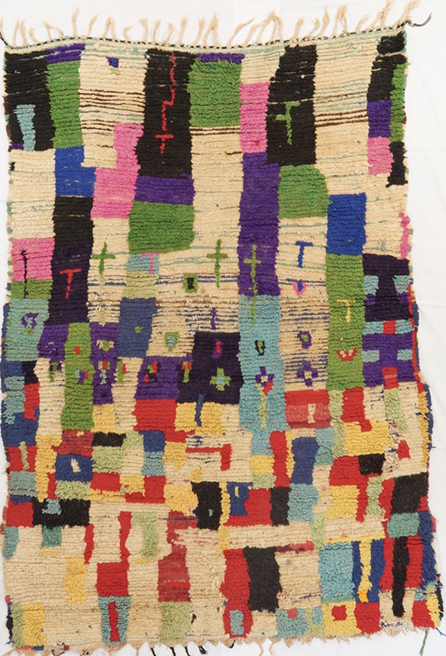

MYTHOS AZILAL – Exhibition in Austria from Art Galery Reinisch Contemporary

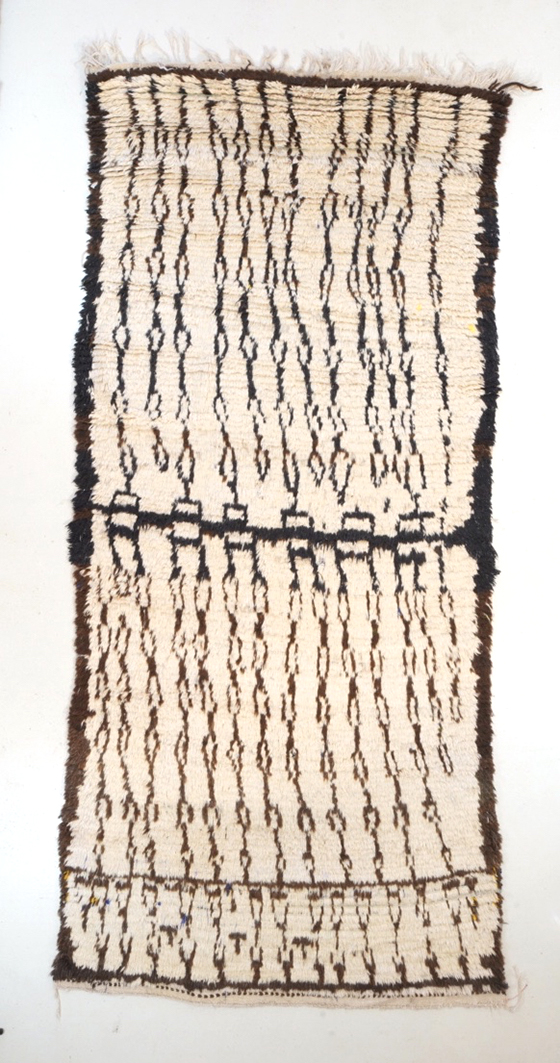

The provincial capital of Azilal is located on the north side of the High Atlas in the region of Béni Mellal-Khénifra, Morocco. Until recently, the area was not defined as a carpet-making region. Before then, Azilal carpets had generally been subsumed under the name Boujad or simply under the terms Middle or High Atlas. Conceptualised under the name Azilal, the high plateau is located between the two ranges of the Atlas Mountains. To the north is the holy city of Boujad – a trade centre synonymous with the so-called tapis fou. Largely free and far removed from traditional constants in their design, these carpets may be regarded as the spearhead of the avant-garde carpet sector. The Boujad style features free floating signs, symbols and patterns derived from the Berber tradition, having already been abstracted, recoded and segmented for a very long time. Other materials, including fabric remnants, were suddenly used in the production process instead of wool – such carpets are now called boucherouites.

AZILAL carpets and stylistic trends

The Reinisch Contemporary gallery has focused a great deal of its attention on Azilal carpets for some thirty years. Here it offers a representative cross-section of this productive area for the first time. Azilal has been recognised as a region that sets stylistic trends in the carpet sector, a place where key phenomena of pattern development seem to come together. Freedom and spontaneity of aesthetics is especially prominent in Azilal. Frequently, order and chaos are juxtaposed in a single piece. Structures become discernible before dissipating from one moment to the next; colours appear to change for no reason and the symbols woven into the designs tend to be segmented or dissolved beyond recognition. An explosion of colours – a vital symbol of the harmony between man and nature – is clearly visible in these “informal” woven images.

Actually, we gladly use the term “informal” to describe this. Here, our Western education frames our judgements on the basis of how we view the progress of art history and draws parallels to informal tachisme painting, itself a monumental, liberatinggesture – the avant-garde’s sword-stroke against everything that had previously existed, as it were. This tabula rasa could only follow in the wake of two world wars. However, the heroic, male act of abstract expressionism cannot be compared with femaleformulations arising from textile art. Weaving is a complex process involving numerous technical steps that are required to produce a result. The actual process of knotting and weaving is always the same – either it is exact and adheres to long-held traditions, or it is free in the sense that it opens up new ways of looking at things. Only the end result makes us think ofpainting and the inherent process of abstraction therein. It should be noted, however, that it is bold and astounding to see what new formulations emerge from such developments. Viewed eclectically, carpets produced in Azilal incorporate the knowledge and forms of its surrounding geographical areas. Hence it is difficult, if not virtually impossible, to define regional distinctions or unique features in this case. They are even wilder, more informal, and further removed from age-old traditions than their big brothers, the Boujads.

AZILAL characterization

What particularly characterises these Berber products is a constant force that drives change, which defines a flow and the ready impression of unforeseeable transformation. Movement never seems to cease in these carpets. Semantic meaning no longer determines the aesthetic order. Essentially, in the creative process, the female weavers have still preserved their awareness of what makes something special – and even of the spiritual dimension. Yet the constants which determine our ability to interpret the patterns have been lost – in most cases, they are released freely and exclusively in accordance with aesthetic considerations. Sure, a preserved symbol may appear here or there in the process, for example to ward off the evil eye or as an amulet or little tree of life etc. – but coherent programmes with inherently logical model structures are absent here.

For we Western consumers, carpets are usually objects of curiosity. In the Modern Age, we ask more from a picture or painting in the course of their development than for them merely to denote an image. Extensions of paintings should be three-dimensional, multifunctional, dynamic and tactile. All these are desiderata that carpets, regardless of their origin, realise from the get-go. Carpets therefore expand our understanding of images in an astonishing way. But does this mean they are images as long as they are looked at and not used?

Günther Holler-Schuster