Duration 26th of November – 19th of Dezember 2014

The West’s attention for Moroccan carpets began in the early 20th century. Exhibitions in Munich and Paris presented handicrafts from the region, with carpets occupying a prominent role. At the same time, interest began to flare among numerous artists, such as Paul Klee, Henri Matisse, and Wassily Kandinsky, and architects, Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, as well as people of the Bauhaus school; among others, Marcel Breuer, Johannes Itten or Gunta Stölzl. The reciprocal influence between modern art and carpet culture is factual, yet it is of limited suitability as an explanation vis-à-vis the development of motifs in Moroccan carpets. Too remote are many of the production sites, where mostly Berber women pursued (and still pursue) this craft, to insinuate they might have been aware of Klee and the others. Even if, during the period of the French protectorate (1912-1955), efforts were made on an institutional level to invigorate and expand regional handicraft using design proposals by French artists.

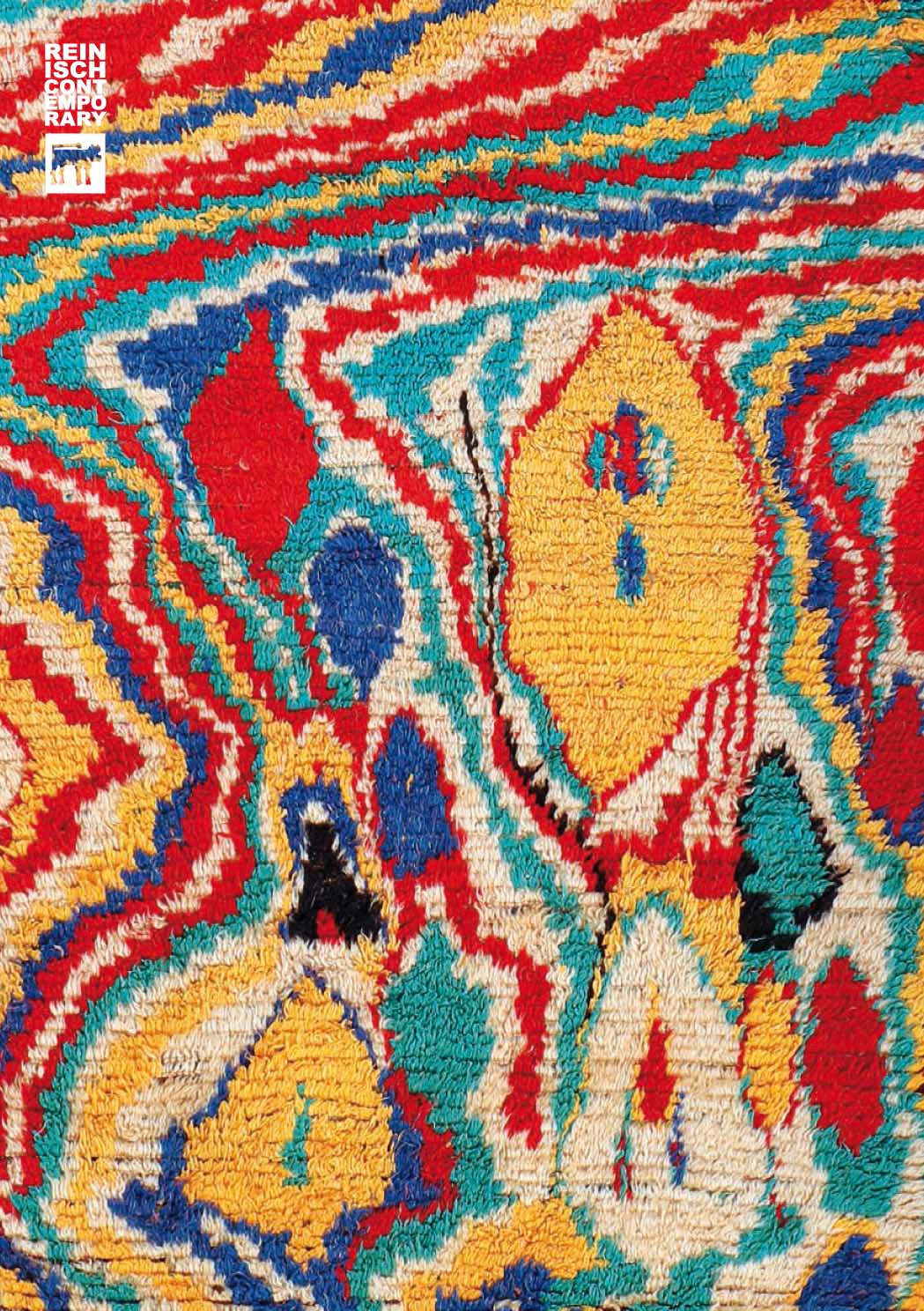

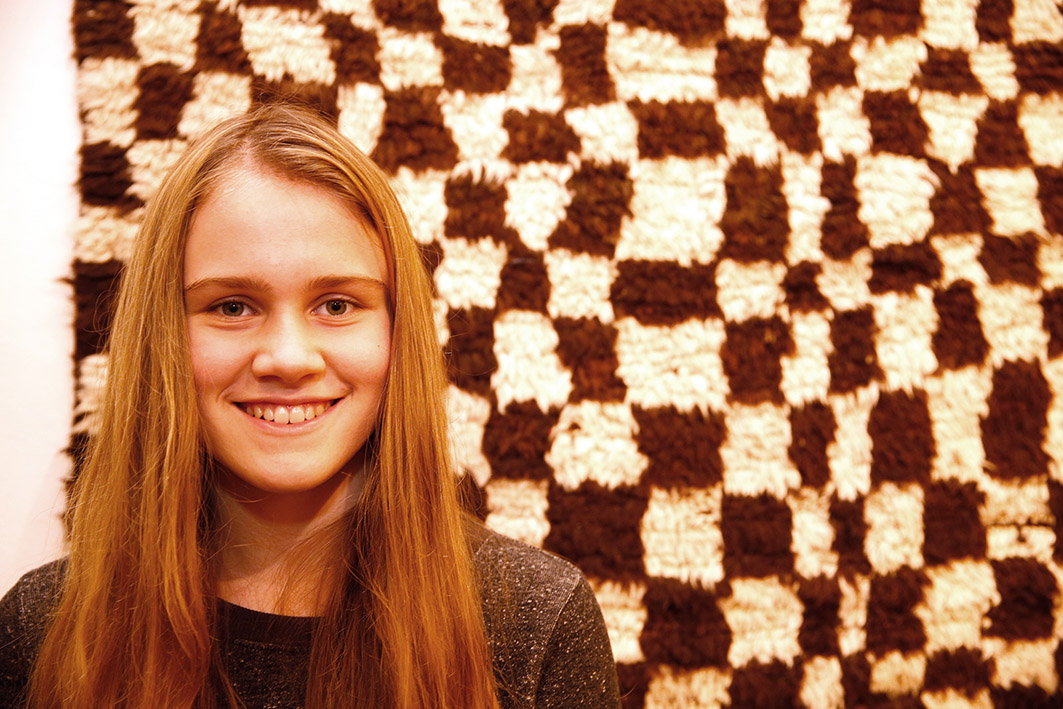

One could, by all means, claim that the Moroccan rug is the modern art of carpets. Key markers of kinship could be detected in the two-dimensionality of image and carpet. Likewise, connections exist in the use of abstraction and the lack of perspective view. Combined with monochromacity, this creates the impression of reduction, dissolution of form and a completely new interpretation of a traditional canon. Crossed lines, chess-board formations, rectangles, diamonds, spots and monochrome areas, which at times tie in with traditional symbolism or simply emerge out of formal intentions, form a design vocabulary which can be traced back to the laws of perception, or the figure-ground relationship. Genuine artistry in oriental carpets strove for the perfection of colour handling in two dimensions, reaching its apex in Persian Safavid carpets of the 17th century. If one were to follow the Western gaze, shaped as it is by modernism, Moroccan carpets would emerge as the most far-reaching dissolution or abstraction thereof. As such, the free forms and colour schemes only conditionally follow traditional formulations, instead conforming to a rather general stylistic vocabulary underpinned by globalisation.

For all that, one must not forget the carpet’s multi-functionality.

For all that, one must not forget the carpet’s multi-functionality.

Modernity’s interest in these carpets appears to be a matter of course. Since the 1960s, there have been efforts, via concepts such as installations or performances, to expand the space and functions of artworks. Border expansions in relation to established categories, implemented by Western art, are also self-evident. Carpets may be places of visual curiosity, yet, at the same time, they also appear beyond visible paintings and tactile sculptures and built spaces. They are images to behold and tread on. They also fulfil, in the nomadic context, the purpose of covering and enfolding, thereby becoming multi-functional and multi-sensual.

With this show, Reinisch Contemporary presents examples from Azilal and Ourika, two Moroccan regions, whose carpets are especially far removed from traditional motif structures and at times attain a perplexing proximity to works of modern painting. It is therefore little wonder to find oneself recognising The Scream, by Edvard Munch, from the years 1893/1910, in one of the carpets shown. At least, it is such formal formations, which our Western awareness condenses into concrete images.

Günther Holler-Schuster