Opening on Friday, 1st of March 2019

7Pm Hauptplatz 6, Graz

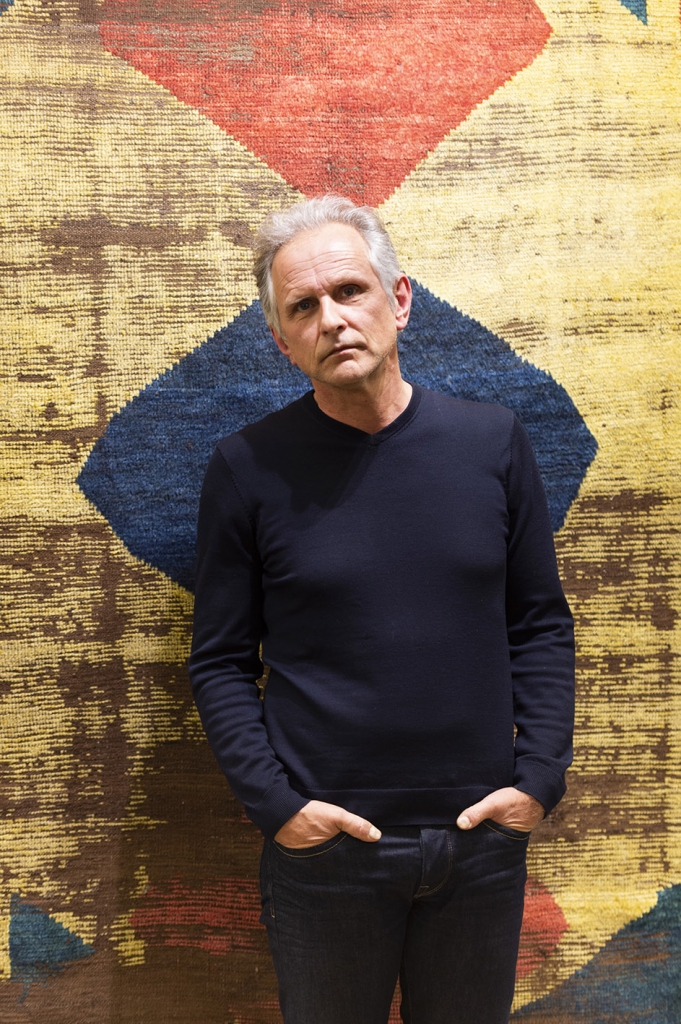

Introduction Günther Holler-Schuster

Exhibition until 30th March 2019

In order to become an artist, one must be an artist, and in order to become one when one already is one, then one comes to the Bauhaus; and to make this artist into a human again, that is the task of the Bauhaus.

Otti Berger

The words of the Austrian designer who died in Auschwitz in 1944 still astonish us today. 100 years after the founding of the Bauhaus, the idea that one wished to turn the “artists” at the Bauhaus back into “humans” seems extremely pertinent. Are not the principal demands on the art of today to be socially relevant, to expose injustices, to intervene directly in social processes and to be politically active? Formal criteria, too, should function insofar as they alter conventions of perception and not simply be further perpetuated as tradition.

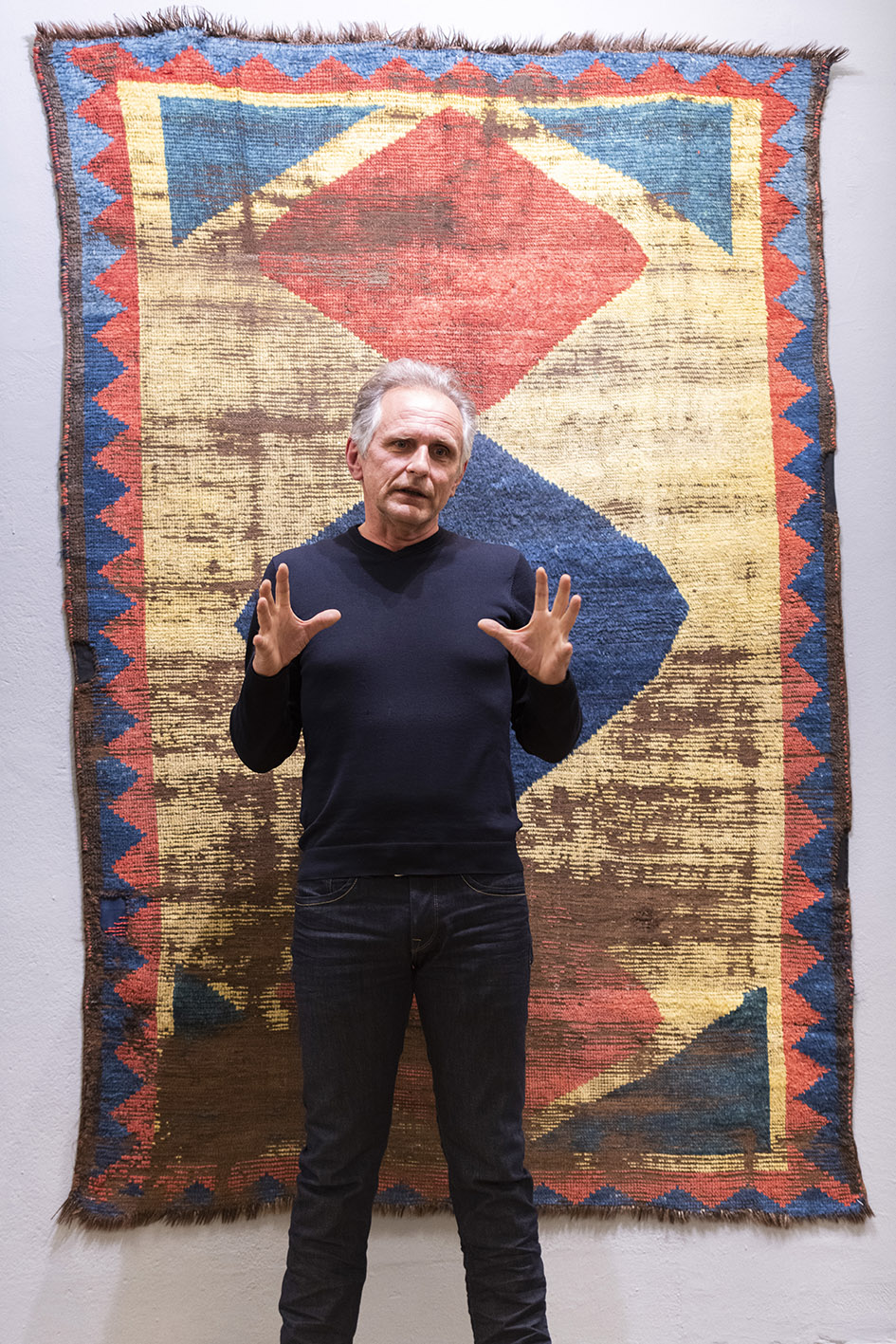

What does this have to do with carpets? The Reinisch Contemporary gallery is among the institutions that engaged very early on with the Southwestern Iranian Gabbeh. The publication “Gabbeh” from 1986 bears witness to this fact, as does the enduring interest in these particular pieces of Iranian tribal art. The rather coarsely and rapidly woven Gabbehs largely come from the Fars province with its imperious Zagros mountain range. The Lurs, Bakhtiari, Qashqai and Khamseh are the half-nomadic groupings who primarily live there.

These carpets never follow classical patterns. Their symbolic power is highly individual and dates back to pre-Islamic times. These knotted works are distinguished by their archaism, simplicity and clarity. Occasionally they are very colourful, can appear oppositely legible and contain figures, animals, objects or plants. Mostly – above all those pieces from around 1900 and earlier – they are abstract and use a reduced palette of primary colours. They are utilitarian objects and were not originally intended for trade. This is why they became known in the West rather late. They strike the Western observer as familiar due to their astounding proximity to forms of modern art. The “learned” eye strives to see the art within. The clarity of the forms and reduction to just a few strong colours generate a visual presence which is known from abstract painting. The Bauhaus stands for an expanded concept of art which leads away from the auratic and towards the true-to-life, whereby the design and the artistry of weaving and textiles also attain prominent status, and are meant to be understood on the same level as art.

The Gabbehs are products of the most original conceptions of form and traditions – no Decadence, no Mannerism. Modernity has attempted to draw inspiration from exactly this in order to get closer to “the essence” of art. Though the two admittedly knew nothing of one another, they were intellectually very close and unconsciously fulfilled the criteria of the other respectively. The nomads in the Zagros have preserved parts of their way of life since almost eternal times. Their everyday objects have stayed practically unaltered – and so too the Gabbeh. The weavers first saw the use value in them; the warming carpet that had to be finished before the onset of winter. Moreover, a far-reaching creative freedom developed among the weavers, since their work was not oriented towards the marketplace. Gabbehs derive their visual power to a large extent from the strong trace that leads back into the past. Western eyes, which have more than 100 years’ experience of abstract art, sense these products to be “modern”. Today we often find ourselves in this hybrid situation when it comes to tribal art, to traditions of craftsmanship and their relation to the industrial and digital present.

Günther Holler-Schuster