21th Oct.-12th Nov. 2013

It is widely known that creativity cannot be tied to classical categories such as drawing or painting alone. The avant-gardes of the 20th century fundamentally expanded the scope of art, both in terms of technique and content. Whether a drawing is done on a rock face or on a piece of wood, in chalk or ballpoint pen, is, consequentially, secondary. The cultural differences, which affect a largely globalised society, create further surprising forms of, for example, drawing and painting. Societies that traditionally do not practice panel or easel painting, such as in many parts of Africa, compensate this central and significant category of image creation through other technical genres – textile arts, body art or wall paintings, among others.

It is widely known that creativity cannot be tied to classical categories such as drawing or painting alone. The avant-gardes of the 20th century fundamentally expanded the scope of art, both in terms of technique and content. Whether a drawing is done on a rock face or on a piece of wood, in chalk or ballpoint pen, is, consequentially, secondary. The cultural differences, which affect a largely globalised society, create further surprising forms of, for example, drawing and painting. Societies that traditionally do not practice panel or easel painting, such as in many parts of Africa, compensate this central and significant category of image creation through other technical genres – textile arts, body art or wall paintings, among others.

When the art gallery Reinisch Contemporary shows works by the Graz-based painter, graphic artist and sculptor Franz Yang-Močnik alongside Moroccan Berber carpets, this may, at first glance, appear like a sales strategy. Yang-Močnik’s charcoal paintings on whitened canvas are expressive and testify to a basic existentialism, which depicts humans as struggling, suffering beings.

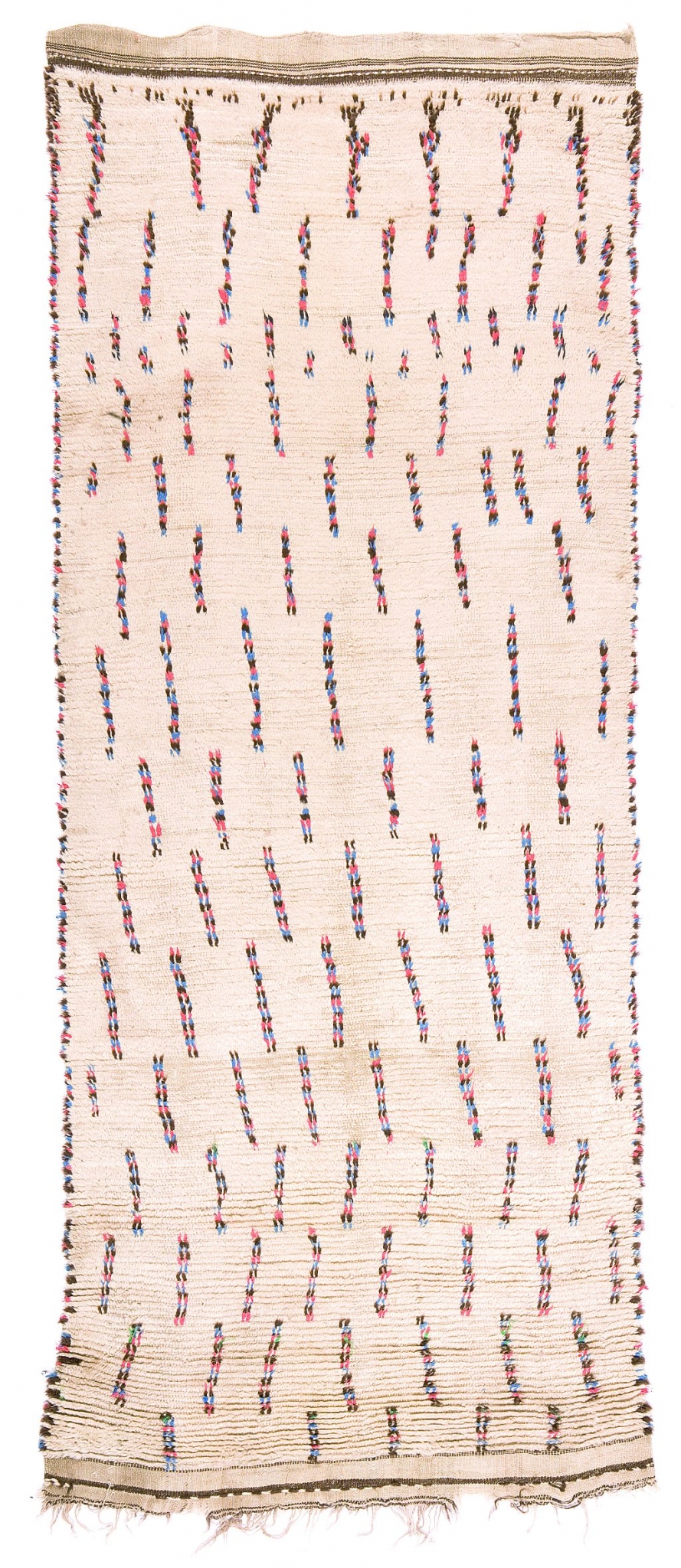

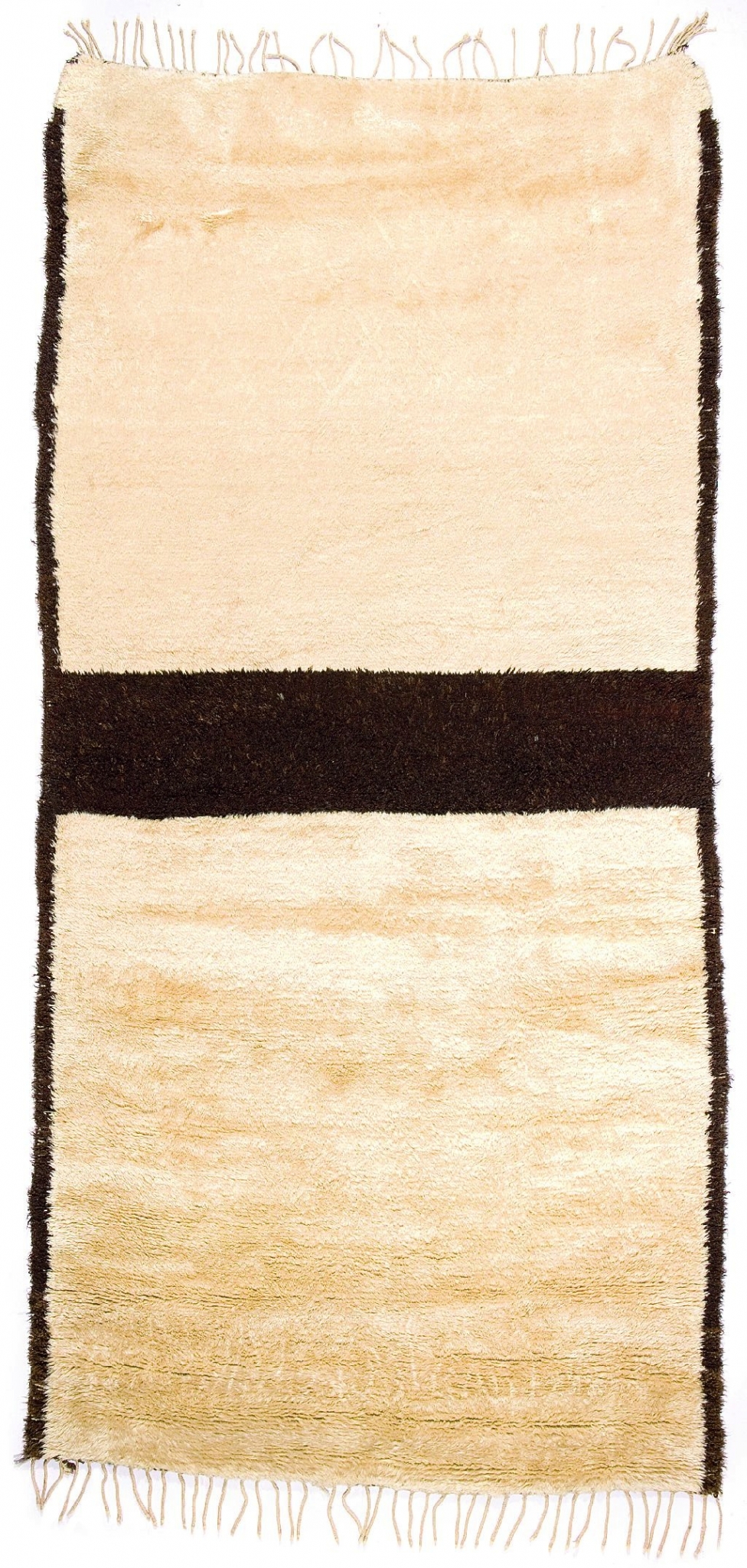

The carpets are predominantly white, with black-brown lines and plots – most are Beni Ourain or Azilal – and follow a tradition that may strike us as abstract. The bars, panels, symbols and stylised forms, however, appear abstract only to a Western perception. In the culture of their country of origin, Morocco, they are narrative. They are symbols of a comprehensive worldview and of a practical, real-life context as well as of a spiritual reality.

Yang-Močnik’s paintings – which can actually, in their materiality and make, be attributed to the genres of both drawing and painting – attain a high degree of abstraction through the gestural application of colour. While Yang-Močnik’s paintings emerge out of a highly subjective perception of his own microcosm, the carpets of the Berber people are beholden, first and foremost, to nature, myths and the spiritual contexts of a macrocosm. But even this relatively generalised dimension is perceived subjectively by the artists, traditionally almost all women. Their own speechlessness within the social hierarchy leads them to express themselves in the signs and symbols of a woven reality.

A comparison between these panel paintings and textile works illuminates highly perplexing parallels, no matter how different they might seem at first glance. Yang-Močnik did not consciously respond to these carpets; rather, the combination opens up a momentary viewpoint and ultimately macerates certain hegemonic cultural pretences of the Western persuasion, which are prepared to see one thing as art and another as handicraft, without considering cultural differences and factoring them into the assessment.

Günther Holler-Schuster